‘Sorry to bother you, but…’ here in London, one of the world’s richest cities, hundreds of people die on the street every year. We’ve all felt their ghosts. A wrinkled coffee cup but no feet. Cigarette ends by a blank sheet of cardboard. A heap of broken tents.

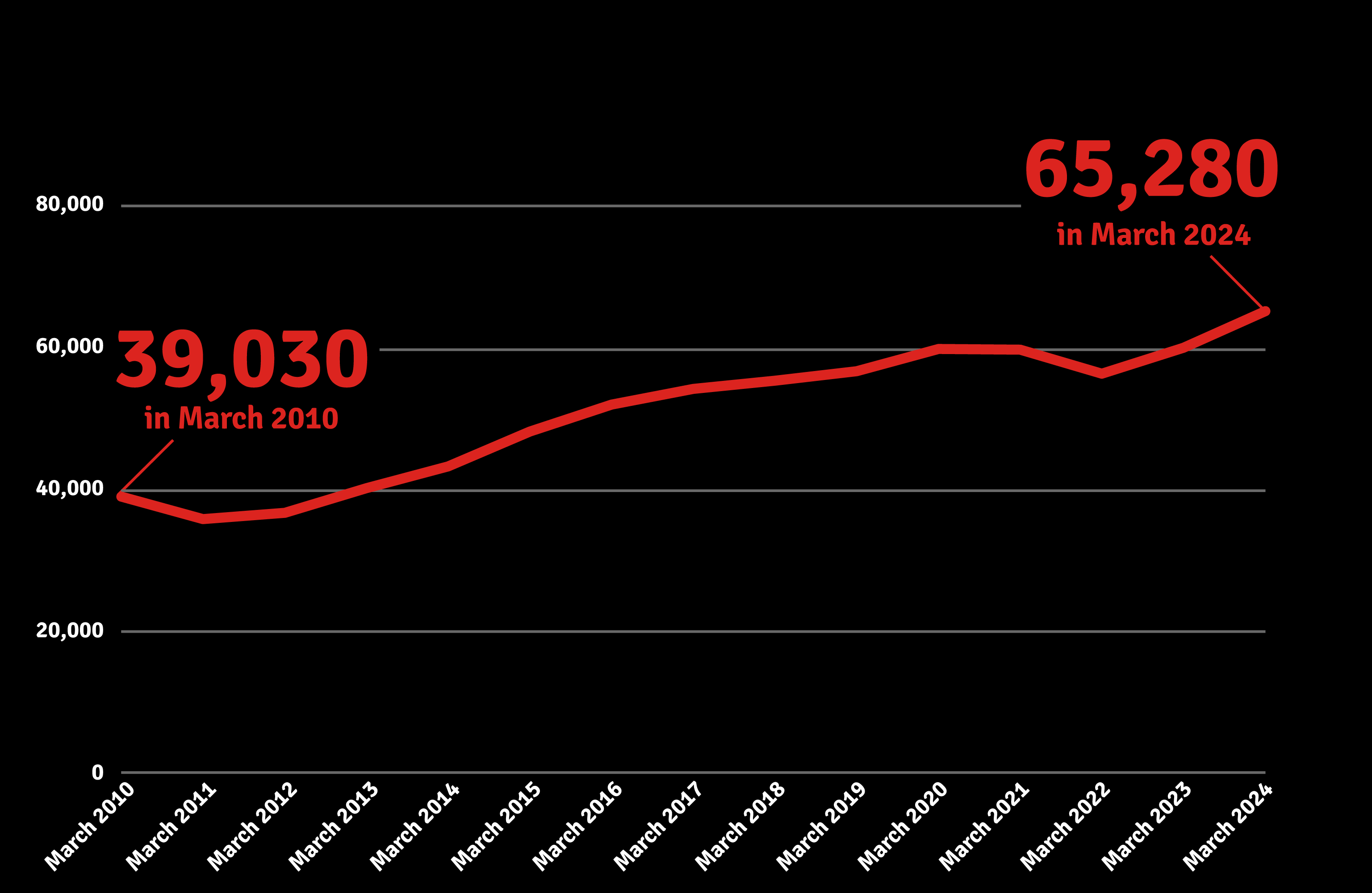

While the latest CHAIN figures, which are a one-night snapshot, put London’s rough sleeping population at over 4,000, Trust for London data shows there were nearly 12,000 people seen sleeping rough in the capital in 2023. Three times as many as there were in 2010 when the Conservatives came to power. Since the Labour Mayor of London Sadiq Khan was elected in 2016, this number has increased by 50 per cent. Each side blames the other, but there’s no dispute the figure is rising.

Sheltering in some of London’s wealthiest high streets and under our busiest roads, MyLondon went looking for these people. Some have fought wars, others fled them. There are drug and alcohol addicts treating their own infections. Here in London, there are domestic violence victims who would rather sleep outside than stay in a hostel because they think it’s too dangerous. And for the refugees who get the right to live here, an eviction and homelessness follows.

These high street camps and shanty towns are just the face of it though. Around London there are hidden homeless: surfing sofas, living in copses, sleeping on public transport, and taking refuge in 24-hour restaurants where they let their phones charge all night long.

We are at crisis levels and Keir Starmer’s government has an opportunity to make the Mayor’s radical ambition - to end rough sleeping in London by 2030 - possible.

In this project we’ve not done anything radical by speaking to people on the street. But we hope by bringing photos and unique voices to as wide an audience as possible, this scandal might be recognised for what it is.

Ground Zero

by Jake Holden

In Tottenham Court Road up to 200,000 people pass through the station barriers every single day. On the same road about 50 rough sleepers crowd their tents among the mice and rats every night.

Across five months I have met many of them.

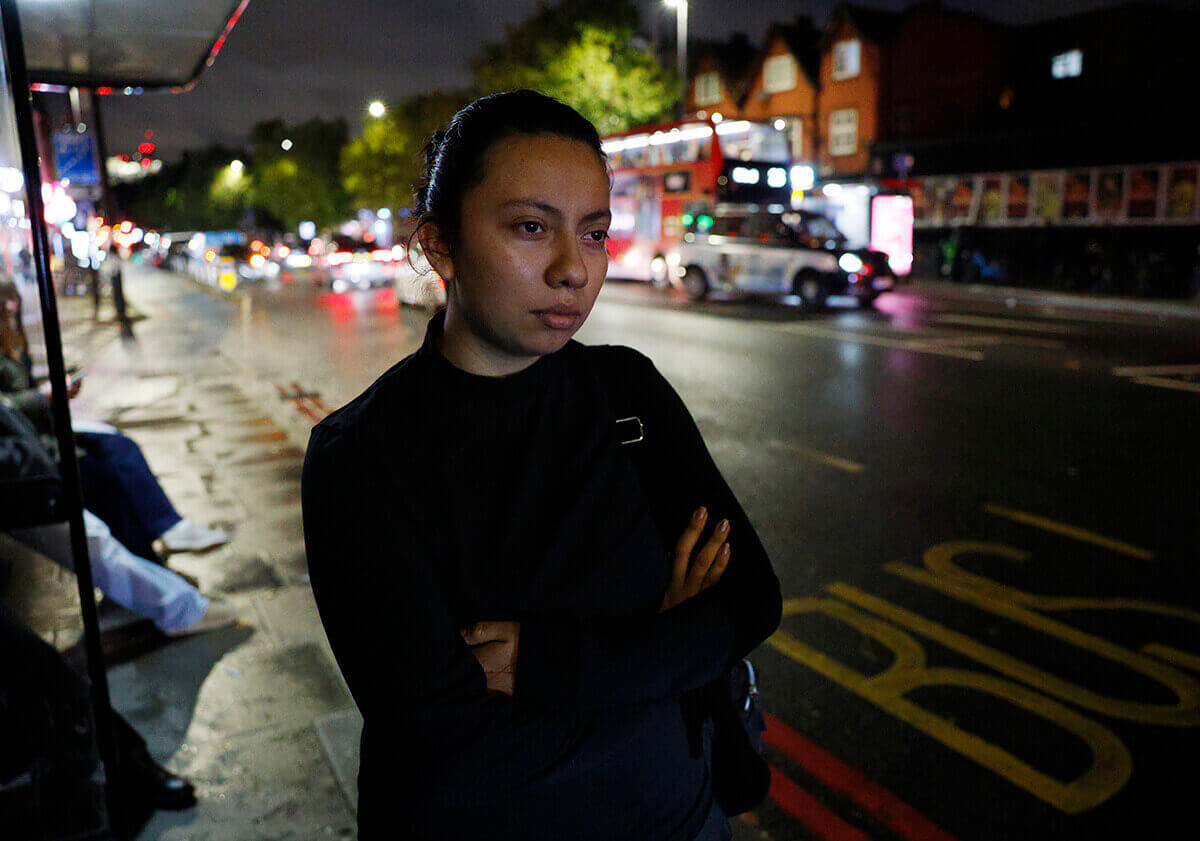

Sarah is a 24-year-old Albanian woman addicted to drinking a paint stripper called GBL. She knows she shouldn’t, but she feels compelled to keep going back to the camp.

She’s wearing a black vest and trousers, her tattooed arms jitter over each other as she shifts her weight from side to side. The noise of traffic fills the evening as she leads us through her life below the giant electric billboard flashing colour on the camp.

“The self-awareness is the most painful part of it. I'm totally aware of how absolutely useless my existence is.”

Head in hands, Sarah tells of running away from her “loving family”, her job, her university degree.

“The year prior to this I spent mostly alone in my room, I was really f*****g lonely”.

While sofa surfing in Paris for two years, she discovered GBL in its techno scene. The drug would go on to kill two of her friends and leave her on the street with a crippling addiction.

"It's like teleportation, one second you're doing something and then you wake up and you've missed, maybe, six hours, maybe one hour.”

Other users don’t miss a thing, “...which is horrible,” Sarah adds, “Because they go crazy with horrible visions. Sometimes they get violent.”

Behind her sit other addicts, some with overwhelming mental health problems.

"A lot of them are just not really there,” Sarah explains. "I've spent weeks trying to have adult conversations and realise only now that I was talking to nothing.”

On cue, a man interrupts with a tumbling conspiracy theory about Taylor Swift’s ‘theft’ of the DNA he invented as a “neuronologist” and a doctor that had been murdered in a “mysterious way.”

On a later visit, another campmate introduced himself to me by taking down his trousers to reveal a stolen sack of potatoes, laughing to his friends. Noticing strangers in the camp he got angry and threatened me with two metal rods from the growing scrap heap outside the tents, scavenged from the streets to be sold. I saw him shouting at pigeons as I retreated.

Despite the strangeness, Sarah says she feels part of a community for the first time.

“And that’s why I think I still haven’t left because I’m scared to be lonely. I’d rather be in bad company than no company.”

Right now, Sarah can’t leave even if she wants to. She was kicked out of the hostel she shared with other addicts and is now trying to get a spot in rehab, but it’s proving difficult.

Sarah sums it up when she speaks about her newborn niece: “Babies are such a pure beautiful thing… But I’m scared to touch him, I feel too dirty.”

Another camp regular is former prisoner Mario Walachowski, 39. He came from Poland in 2020 but was locked up in 2023 for drunkenly punching a police officer after being arrested for shoplifting. Mario says he did it because he was struggling with fears his seriously ill young daughter would die.

“She’s never going to walk, she’s never going to talk, she’s not going to eat by herself or be by herself. She’s four years old.”

His ex-wife had called to say they should sign papers to cut off her treatment, but he refused, he says. “Basically she was going to die. So, yeah, I was f*****g furious.”

Mario was stabbed for the first time when he was sent to Wormwood Scrubs prison for eight months after the incident. Why was he attacked?

“Because it’s prison. You get fights, you get riots and everything. You’ve got paedophiles, drug dealers, everyone mixed. You never know what will happen.”

In spite of that, Mario says immigration detention centres, where he spent two months, are even worse.

“You got guys in there who don’t care because they’re going to be deported so they have nothing to lose. They can stab you, they can kill you.”

His second stabbing was on the street following his release in April. “It’s a daily basis when you’re homeless. After 10pm, if you don’t know proper guys you can get stabbed, robbed, beaten, everything.”

Like many others on the street, Mario is an alcoholic. “Anyone living on the street, trust me they’ve tried everything just to forget life or the moment. I’ve tried crack and stuff like that. It’s indescribable. I wouldn’t do it again. But alcohol and drugs are the same thing. It’s addiction.”

Now he’s moved camps and shares with a friend down the road because his tent was ruined after months of use. He’s trying to secure his passport so he can claim benefits and complete a construction course to find work as a builder.

Next to Sarah and Mario’s camp sits the American International Church, which runs a soup kitchen feeding 200 people a day.

Reverend Jennifer Mills-Knutsen observes the camp has a particular reputation for “hate speech, harassment on the street and brandishing weapons”. This has led to efforts from the church to distinguish between rough sleeping and anti-social behaviour. Nearby food stall owner ‘Thai Jack’ agrees, complaining he’s forced to cook just metres from where homeless people urinate.

Jennifer, Jack and other stakeholders have contacted Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who’s also MP for the area. Their aim is not just to turf the rough sleepers out, despite the “untenable situation”, but to find them “stability and long-term support”.

Although this encampment has a poor reputation, a tidier, more orderly camp forms each night on the pavement opposite. The owners of Heals high-end furniture shop allow sleepers to shelter under their awnings provided they clear out during business hours and keep it clean. Ex-soldier Gareth Jones, 63, lives there.

Claiming to be a veteran of the Falklands, the first Gulf War, and Bosnia in the 1980s and 1990s, Gareth tells of his best friend being blown up by a roadside bomb.

The former soldier has a diagnosis of terminal lung cancer with no support and a world of chaos around him. “I’ve seen people getting pissed on. I’ve seen people getting spat on. I’ve seen people getting set on fire.”

After serving his country then working in civilian jobs, three years ago Gareth moved from Wales to London and ended up on the street.

“Homelessness can happen to anyone at any time. You can work in an office, you can have a nice home, a wife, kids, a mortgage. But all of a sudden you lose your job; you can’t pay your mortgage; your wife disappears because you can’t pay the bills. You’re on your own. What do you do? All these so-called friends, where are they?”

The government has washed its hands of him as an ex-soldier, he says, affording him no help.

“I got nothing, I didn’t get any bereavement counselling. Nothing. It’s disgusting the way they treat us ex-vets.”

Despite the undignified conditions, Gareth fights for his self-respect.“I’ve never begged in my life. I’ve got to go to all the handouts. I go to Camden Town soup kitchen. It’s demoralising. It’s embarrassing. But you do it because it’s called survival.”

On the night of November 17, the camp where I met Sarah and Mario burned to the ground. I’ve spoken to Mario since, but I am yet to hear from Sarah. London Fire Brigade confirmed there were no injuries.

Rough sleeper Gary Birdsall, 51, was camped nearby when it happened. "I was asleep, and I heard the fire engines and screaming. A cleaner was there at 6 o'clock this morning who said there were a lot of nasty needles on site.”

As charred debris covered the ground where people had once slept, only two tents were left standing.

* Some names have been changed

The Kiss

by Callum Cuddeford

I find the old man sitting on a slatted wooden bench under the A13 holding a Metro newspaper. He is half-Kenyan and after the end of his marriage he slept here for months. He got a place last week, but every day he makes the bus journey from Beckton to spend time with his friends under the flyover.

This is Canning Town where Poles, Russians, Romanians and Ukrainians drink; British men and women shoplift meat and sell it on doorsteps to buy crack cocaine; and Sudanese and Nigerian men wait patiently with their documents stuffed into rucksacks.

They all live in tents and on mattresses settled between the knuckles of tarmac and steel that make up the road flowing and rumbling above. After a clearout by the council on my second visit, this heap of bric-a-brac and cardboard has grown and grown. “The biggest I’ve seen in 12 years,” says the binman.

I ask the old man to get Ali, the young Bangladeshi dad I met two weeks ago. Last time I saw him he was hunched over a steaming box of daal handed out by the church. He was happy and devouring rice with Elli, a Filipino man who used to work nights cleaning the escalators underneath Canary Wharf.

Among worse company Ali looked relatively healthy, but he was staring into the end of a crack pipe and he missed his daughter. Today when he pulls himself from his tent, his hair is longer and knotted. His face appears chalkier and his easy smile has worn thin. At first he looks like he doesn’t recognise me, but then Ali invites me into the tent to talk to his friend.

It is my first time at Ali’s house, or any tent on the street. I climb inside and there is warmth from the naked duvets pressed against green polyester walls. Out of the front door I can see Elli across the street, smiling on his porch. There is a mattress covered in clothes and blankets, laid next to a wide pillar. My first impression of Ali’s house is a warm hug, then I notice the smell of rich perfume against the unfamiliar breath of a man reclining next to me.

This is Musa. Musa punches letters into his Nokia brick while Ali sweeps rubbish into a dustpan just outside the tent door. Ali continues to speak casually. He chats and brushes the dirt and litter at my feet and now it feels like I am in Ali’s kitchen and he’s invited me in for tea.

Soon enough he offers me food, throwing me a bag of Lion Caramel and Chocolate cereal into the tent along with a ripe banana. “In my country, when someone comes to your house,” Ali says, but then Musa cuts in. Some cereal has flown from the bag during the throw. “Don’t do that bro,” says Musa, “we need to keep it clean.”

As Ali disappears it feels like he’s left me in his living room with his weird mate. Musa continues thumbing letters into his phone then asks me how to spell ‘Listen’.

“L-I-S-T-E-N,” I say.

Musa is texting a friend. After seven nights surfing in Ali’s tent, he tells me he’s looking for a real sofa. Musa grins as he finally sends his text. His smile exposes the steel retainer that runs across his front teeth. “So you want to know my story?” he says confidently.

“Yes.”

“I was in hospital but they kicked me out. They had enough of me,” Musa tells me.

“Which hospital was it?”

“Newham Centre for Mental Health,” he says, pointing in what I presume is the hospital's direction.

“Where did you go after that?”

“They put me in a Travelodge, next to City of London Airport, but then I was out on the street.”

“Where did you sleep?”

“Railway arches. Paddington and Victoria. I went to Hackney and Whitechapel too.”

As I sit cross-legged with Musa, I try to take a note of what he is saying and what I can see around me. It’s a twisted mess of white, grey and yellow; duvets, sheets, and pillows. Only the most valuable items are kept inside the tent.

“I got mental health, I should not be sleeping in the streets. I’m a paranoid schizophrenic,” Musa announces, “I could kill a man any moment. I’ve got bad mental health and I’m addicted to drugs and I do not know what to do.”

I listen closely to the part where he says ‘I could kill a man at any moment’. Then Musa continues his story.

“I killed someone before, and I do not want to kill again. I have a devil in me. I have had a devil with me since I was five years old.”

Ali throws the lighter into the tent and Musa is looking at his phone again, texting his friend.

“Who did you kill?” I ask him.

The question goes over his head, but he has a question of his own.

“Are you writing this down? What did I say? Read it back to me.”

Slowly, I read him back his words, deciphering the tangle of black ink squeezed into my little brown notebook. Musa grunts with approval.

By now another man, Omar, is squatting beside the tent with his fingers clawed over a can of Kronenbourg. Musa looks at Omar’s shoes. The suede is clean and the white leather glossy like paint.

“Bruv your trainers look fresh,” Musa says, continuing his long stare. I can see I’ve lost him so I try to ask my question again.

“So, uh, what happened with that guy you killed?”

My question draws a blank. Musa continues adoring Omar’s trainers. The conversation continues. Musa is obsessed. But then Omar stands up and walks away, taking his trainers too. As soon as the shoes are gone Musa’s mind seems to float around the tent before circling back to me. Then he answers my awkward question.

“Someone in Tottenham. We had been arguing for a long time. He was a street alcoholic. We fight every time. I fight him, and he fights me. I was drunk. I was so high. So much skunk. So much crack. So much drink. I don’t know what I done and I end up hurting someone.”

Musa says he was charged with murder but then it was dropped to manslaughter.

“Diminished responsibility?” I ask. “Yeah, diminished… yeah that.”

This was 2011 and Musa was jailed for 10 years. Later that day I find a local newspaper report confirming his story.

It is now more than 13 years since Musa stabbed a man in the neck while he was high on crack. Musa still smokes crack. He says prison made him strong and wise.

“What are you going to give me? You got a few coins, a tenner.”

“I’ve got nothing on me,” I say.

Musa is wise enough to know I’m lying.

“You can get something out for me.”

It’s like hearing ‘I take card’ and it catches me out.

“I can buy you some food, as a favour, but I don’t want this to be a transaction.”

“It’s not a transaction,” Musa reassures me, “I’m just desperate for some crack.”

Musa looks hungry.

“I’ve been coming here for weeks and I’ve not paid anyone for a story,” I say, “It’s unethical.”

Musa smiles. “Journalists pay for stories all the time.”

‘He's right,’ I think.

“You’re right,” I say, “but I’m not writing one of those stories. I’m happy to get you some chicken, but you don’t need to tell me anything.”

Musa looks increasingly agitated.

“I’ve got stories. Crime, robberies, drugs, murder,” he spits, casting out offers like it’s closing time at the fish market.

“I’m not looking for that,” I tell him, “I can’t give you money.”

By this point Musa has produced a small threaded cylinder that looks like a hollowed out metal bolt. He pushes something into the end and breathes out deeply. Holding up Ali’s purple lighter to the end of the pipe he inhales and holds the smoke inside his billowing chest.

Musa’s face tingles with excitement and he is gone. Instantly I am quiet. For a few seconds I am alone in the tent. I study his rolling eyes and limber facial muscles. It seems he’s experiencing a living death so I turn away to write in my notebook, believing Musa may never wake up.

‘Reaction is almost aroused,’ I write, but then Musa taps my shoulder and the fear rushes through me, causing my spine to clench in tandem with my heart. “Oh sorry did I scare you,” Musa says with sickly sweetness.

“No no. I’m fine,” I lie. I don’t want to upset him. He keeps sliding his hands around the front pocket on his hoodie and I have already imagined a small knife he could be hiding there.

“What was that?” I ask.

“Just some weed,” says Musa.

It’s not like any weed I’ve ever smelled, I think. “Are you sure?” I say, “Not crack or spice, or something else?”

“Nah,” Musa insists, “it isn’t.”

I ask Musa why he smokes crack.

“It calms me down,” he says, “I think too much. I’m an overthinker. It chills me. It gives me a little freedom, that five second buzz. I feel free. It opens my brain a bit. I become active and go shoplifting. Sometimes I have to feed my habit. Get two, three, four bottles of wine and sell them for fifty sixty quid.”

Musa unravels his wandering look and directs it back to me. “Do you smoke?”

“No, it f***s me up,” I say.

Then we are interrupted by the buzz of Musa’s Nokia. “It’s Cosmin. You answer it. He’s a journalist too,” Musa tells me, wagging his finger at the phone. I take the phone and do what Musa says.

“Hello, Cosmin. It’s Callum here. I’m with Musa,” I say.

“Where is he,” Cosmin says, “Is he coming to me?”

At this, Musa gestures for the phone. I pass it to him and he tells Cosmin he’s on his way.

I have wondered what these men do for pleasure. With an average life expectancy of 45, most rough sleepers are stalked by the cold weather, infections and substance issues. And yet of all the mortal threats, boredom seems one of the most cruel.

Over the weeks I’ve met a Nigerian asylum seeker who meets a woman for ‘research’ in Newham Library. Another Nigerian man with a broken penis (damaged during a stabbing) has spoken of his incurable lust. For the most part though, it has been hard to ask people what they do in the bedroom when they don’t have one.

Now I’m in Musa’s bedroom, I ask him about his sex life.

“I’m homosexual.”

“So are you and Ali…?” I ask.

Musa snaps into a frown. “I’m like his older brother,” he growls, “I will never go there.”

Drawing back from another intrusive question I leave Musa to ruminate.

“I could be bisexual too,” he says, “I do love the p***y sometimes.”

I note this down.

“But when I’m on crack, I think of getting a d**k in me.”

Musa looks aroused at the thought. ‘Does crack make you horny?’ I think about asking him, but then I decide this question might arouse him even more.

Musa asks me to read his words back again. I do it. The bit about ‘getting a d**k in me’, he asks me to read that twice. I begin to wonder if I’m providing him a service.

“Is that part of it? When you do drugs. Is there a sexual feeling?” I ask.

“I just feel I want to be high forever. I enjoy it,” Musa says.

Musa tells me he only came out recently, hiding his sexuality from himself and other prisoners. He had a few encounters with men that left him feeling confused and since then men are all he thinks about.

“I like an Englishman, still. Forties or fifties. A mature man.”

“Have you found that man?”

“No, not yet. But I will find him.”

“Do the guys here know?”

“No, I keep it to myself. It’s best like that. I do not want to rock the boat - as they say.”

A pause fills the air and Musa stares at me intently.

“You’re a good looking guy.”

I think about returning the compliment, but I know Musa would detect insincerity.

“I like English guys,” he says, subtly changing the rhythm of his sentence. “Do you want to kiss?”

I look into Musa’s eyes and produce a nervous laugh. I get back a loving look.

“I’m getting married soon,” I say, “so no, I don’t want to.”

There are so many reasons why I don’t want to kiss Musa, but ‘I’m getting married’ seems like the least convincing.

Sensing an opportunity to prey on my politeness, Musa prosecutes his case.“That means it’s your last chance before you get married.”

Musa disconnects the tent door from its hook, letting the green polyester sheet unfurl towards his bobbled socks. He begins to lean towards me and that loving look has gone. I’m in Musa’s bed now and he’s just drawn the blinds. Suddenly the mix of perfume and pipe smoke has nowhere to go and the sunlight is dull.

I bolt upright to clutch my bag, ready to run away, but my head races with thoughts about the exactitude of a small knife entering a major artery: The whiteness that fills a face as the heart beats blood from an open wound.

Then I think about the schizophrenic men with forlorn faces, sitting at the back of courtrooms before they are sent to hospital. Then I think about Musa. I think about his pocket. Then I think about the knife. The pocket.

“Just one on the cheek.”

This time I cannot resist him and offer his cushiony lips the stubble below my left cheekbone. His greying beard tickles mine and the kiss lingers. But after I am grateful it was only his lips.

Then I hear footsteps outside and Ali rolls up the tent door to reveal Musa giggling like a child.

“Are you two alright?” Ali asks, “I want to get back inside now.”

“Yeah yeah, all good,” I say.

I feel dirty and I’m desperate to leave.

On the way to the chicken shop I tell my colleague Facundo about my kiss with Musa.

“On the lips?” he asks.

“No, no. Just the cheek,” I say.

“Oh that’s not bad.”

Two weeks later I find Ali looking even more defeated. He’s had a free haircut but to me it looks like addiction is wearing him down again. He insists ‘I’m not hooked’. I ask him where Musa has gone.

“Oh, he got his money so he left,” Ali says. “He’ll be back when he runs out of money.”

I think back to my meeting with Musa and that he mentioned plans to go to Birmingham the next day. That he also had plans to stay on a friend’s sofa in East London. But really there was nothing certain about his plans, only his desire for more crack.

Another two weeks pass and the camp has been cleared by the council again. It gives me a chance to scan the walls that were previously blocked by tents. I find a large kitchen knife and paint scraper slotted into the wall.

* Some names have been changed

The City

by Adrian Zorzut

In a city home to 227,000 millionaires, a man unzips his tent and shuffles out. He is tall and well-dressed and appears unphased by the suits rattling past on bicycles as he straightens up.

It is Friday evening and like many living along Castle Baynard Street in the City of London he is getting ready to escape the chaos of the night ahead. His tent smells of mothballs and inside there are neat piles of old newspaper. Grabbing a bottle of fabric softener, he makes off for the nearest exit.

I stop him and ask how he ended up on the streets. Tersely he replies that his story "doesn't matter". It’s a response I hear time and time again during my visits to the camp.

In Castle Baynard Street, a transient population of mostly asylum seekers have made their home with tents and makeshift kitchens. Nearby is St Paul’s Cathedral with its inspiring architecture, nine-to-five City slickers and a patchwork of prime restaurants and cafes. To the east is Southwark Bridge and to the west is Blackfriars Bridge. Over the water is Shakespeare’s Globe. The Salvation Army’s international headquarters sits above.

From a tent though, these monuments mean nothing.

Aziz has lived here for three years. Homeless for at least 16. As we leave the tunnel, he catches us and invites us back for a chat.

Sitting on a scrunched-up sleeping bag, Aziz tells us how his step-father kicked him out but his mother secretly let him return to live in the attic at his family home in Birmingham. This was on the condition he never appeared when her husband was home or told anyone he was there, he claims.

Aziz takes a moment to collect himself. Then he looks around. There is a small gas stove in one corner and gas canisters in another. He considers himself lucky because he has a cooker.

He moved to Castle Baynard Street because it provides shelter, but it comes at a cost. “The pedicab drivers put their music on and intentionally put it loud,” he says. “I’ve had others yell and shout at me and say they do it because we’re homeless.”

Here the odd passerby will spit at their feet and urinate nearby. Clothes get robbed, and there are fights over drink, heroin and spice, a synthetic drug. One Ethiopian man we spoke to had been the victim of two tent thefts.

“Since being here, I’ve not slept… There is so much noise. I think I’ve become an insomniac.”

One time Aziz woke up to find two men fighting over drugs.

“My heart was still racing.”

He describes how one man used a shovel to smack the victim’s head before lunging at him with a knife and stabbing him five to six times, including in the neck.

“I was thinking of helping him but there was no point getting involved because I could have been locked up myself.”

Instead, Aziz keeps to himself.

“It’s dangerous living here. The people around here can get weird. If you start hanging out with those people, they try to bully you and try to take your money.”

Rough sleeping charities, like The Connection at St Martins hand out food and give him somewhere to charge his phone. Aziz says he was placed in hostels by two London councils but felt unsafe and returned to the street.

To keep clean, Aziz uses the shower at a nearby PureGym. To make ends meet, he works two to three days a week as a delivery driver and stashes his bike away when he’s done.

He’s not the only person here who manages to work while sleeping rough.

Hash, a Brazilian man who came here legally in the hopes of becoming a lorry driver, couldn’t pass the driving exam because of his poor English. Now he works as a kitchen porter and is saving money so he can move to live with family in Japan.

Another man, James, from Sierra Leone, left the West African country with dreams of studying engineering. After 29 years in the UK, his roommate died and he now lives in a walkway off the main street.

While the balmy summer nights can be noisy with a stream of bicycles, the winter months can be unbearable.

“Last year, it was so cold that my feet froze. I couldn’t walk for two to three days,” Aziz says.

It means when the temperature drops, Aziz wraps himself in blankets and hides away in what he calls his ‘palace’ for hours. When I ask how he manages, Aziz looks at his palace.

“I just go through it and I leave the rest to what destiny brings.”

The City of London Corporation says it is determined to prevent rough sleeping and, when it does occur, ensures it is “rare, brief, and non-recurring”.

A spokesperson said the Castle Baynard Street area is a priority and the Corporation is using a multi-agency approach with outreach workers, immigration advisors and substance misuse professionals.

* Some names have been changed

There has been a 20 per cent rise in new rough sleepers in the last year, according to St Mungo's homeless charity. Stephanie Ratcliffe, Head of Migrant and Advice Services at the charity, blames the cost-of-living crisis and a shortage of suitable housing in the capital.

“People who have never been at risk of homelessness before - that’s never been a tangible possibility for them - are finding themselves in that position and sleeping on the street, which I think is very shocking and heartbreaking,” she said.

At least half of rough sleepers the charity surveyed in the first three months of this year reported a mental health need while 70 per cent said that theirs was impacting their recovery.

This mirrored Greater London Authority data which showed of those assessed for support across the capital, 51 per cent needed support for mental health. Some 33 per cent needed help for drugs, while 29 per cent needed support for alcohol-related issues.

MyLondon understands that a dedicated Inter-Ministerial Group across the Government has been convened by the Deputy Prime Minister, Angela Rayner. This has an aim to decide on a long-term strategy to end homelessness across the country. The capital is also set to receive nearly £2.8 million from an emergency £10 million winter pressures package for rough sleepers.

In addition, London local authorities are receiving almost £200m (£198.8m) in Homelessness Prevention Grant funding in 2024-25.

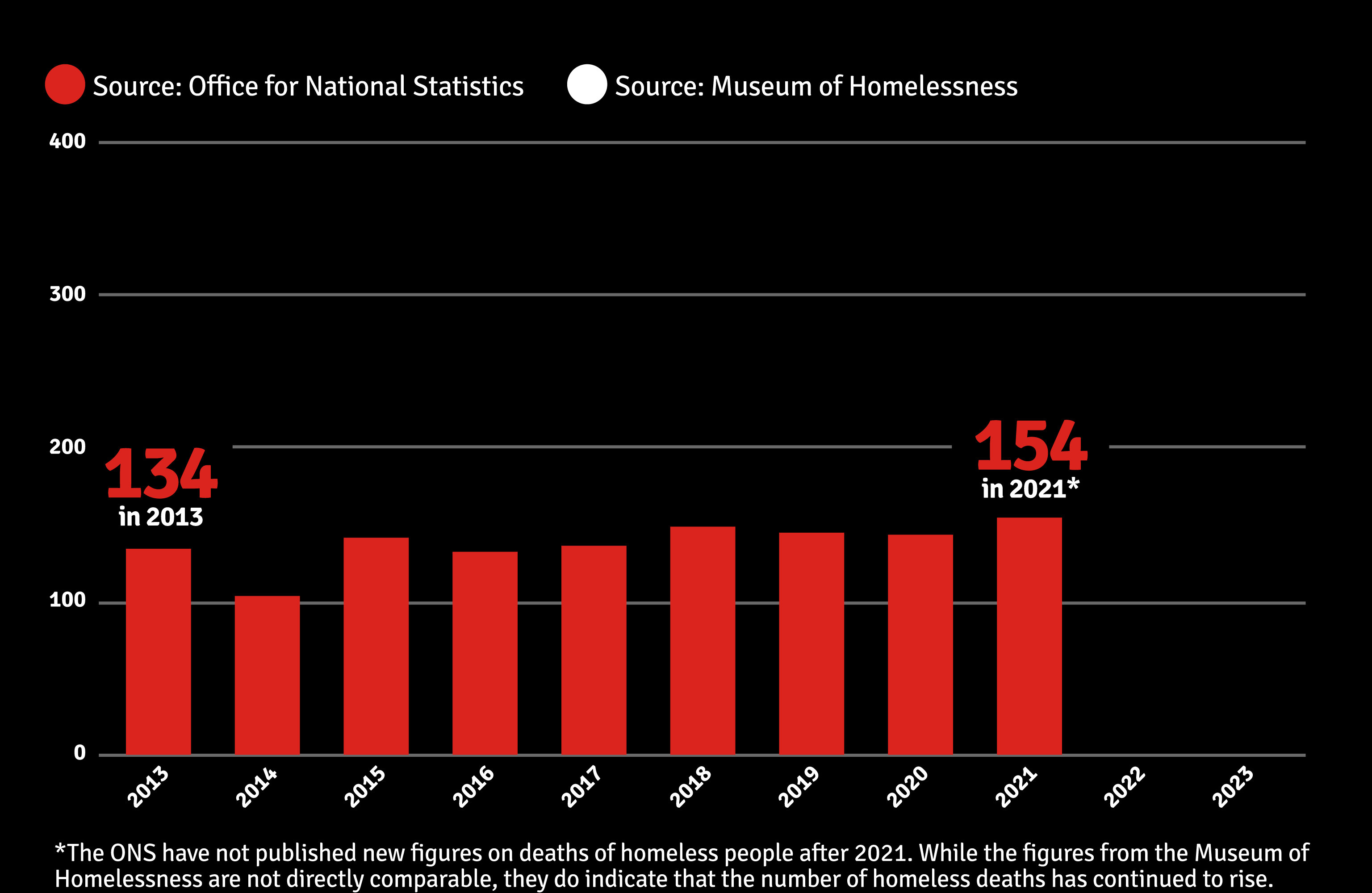

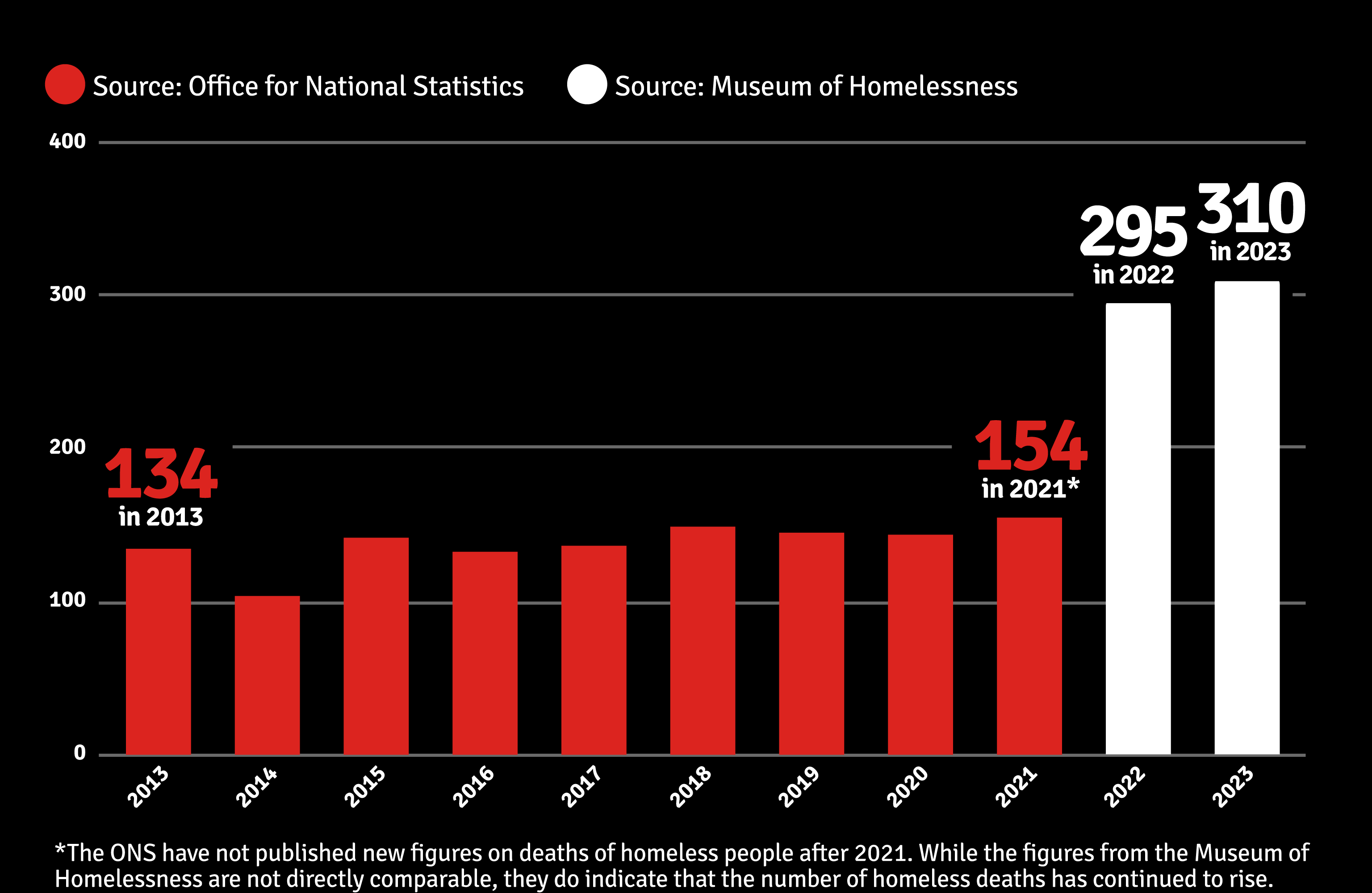

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has not counted homeless deaths since 2021, but is currently working to revise the way it collects data. The next set of figures for England and Wales is expected in 2025.

The Museum of Homelessness carried out its own study of homeless deaths in 2022 and 2023, suggesting the death toll is much higher than initially thought.

In 2021, ONS estimated 154 rough sleepers died in London. This figure was put at 295 by The Museum of Homelessness in 2022, rising to 310 in 2023. The charity used a different method to confirm the number of deaths; sending Freedom of Information requests to each local authority and scouring media reports.

When we presented some of our findings to the Government, a spokesperson from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government said: “This government has inherited devastating levels of rough sleeping, and we are taking action to get back on track to end homelessness in London and across the country.

“As announced in the Budget, we are providing an additional £233 million of funding to help prevent rough sleeping and future rises of families in temporary accommodation. This takes total spending on reducing homelessness to nearly £1 billion in 2025-26.”

The Mayor

by Adam Toms

After hosting an emergency round table on the rough sleeping crisis at City Hall, we presented the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, with our findings and asked why homelessness has become worse under his watch.

“You've been in office for more than eight years now, and you're blaming the previous government for a lack of investment. But it's not entirely their fault, is it? Do you share some responsibility for the situation?"

"Well, let me respond to the four minutes of introduction you've just given me,” Mr Khan says.

“In London, we know there's been an increase in rough sleeping. We also know that, since 2016, we've increased by more than fourfold City Hall's rough sleeping budget. And that's enabled us to take off our streets 17,600 people sleeping rough. Those aren't just numbers, those are people who've been taken off our streets."

The Greater London Authority has funded wraparound care for those with drug or alcohol dependencies or mental health problems, he adds.

"I do hold the previous government responsible for a lot of these challenges," he then says, suggesting homelessness across the country has increased since 2010 because of underinvestment.

"More than three quarters of those we've taken off our streets have stayed off our streets. But we know, for the reasons you've alluded to, that rough sleeping is going up.”

As the Mayor praises the previous Labour government’s achievement of reducing rough sleeping by more than 60 per cent, we decide to interject.

“On your watch,” we say, “It’s got worse on your watch.”

“Since 2010,” the Mayor begins. Then he pauses to collect himself.

“Since 2010 rough sleeping has gone up by 170 per cent. The last time I checked, I became Mayor in 2016, not 2010."

Mr Khan is then presented with the stories of Maria and Sarah, previously mentioned in this project, and Bradford-born Gary who also spoke to MyLondon about living life with 'one eye closed and one eye open'.

The 51-year-old has been homeless for more than 30 years. He says the Mayor should come out onto the streets and see the reality of rough sleeping if he’s interested in ending it.

"He doesn't know the extent of the problem. I don't think he'd survive. I’d love Sadiq to get his arse out one night."

Responding to Gary, Mr Khan says: "I've not been a rough sleeper for 30 years, as Gary has. I've just been speaking to Lorna [Tucker McCarvey], who has been a rough sleeper, and she reminded me that of all the people sleeping rough when she was a rough sleeper, only three have survived, because the life expectancy of rough sleepers, I think, is 39 years of age [St Mungo’s charity puts the age at 45 for men and 43 for women].

"They will die far sooner than journalists or politicians, so that's one of the reasons we've got an ambition to end rough sleeping by 2030."

It can be done, the Mayor insists, with the right leadership, resources and policy.

“Will you do what Gary says and actually go out and see the people living on our streets,” we ask.

"I regularly meet rough sleepers, not just because I'm a journalist wanting to write a story,” the Mayor retorts.

“Because I'm a Londoner who believes in the values of being a keeper to your neighbour, not walking on the other side of the road when you see somebody suffering. But also those are the London values: helping those who, for whatever reason, may have had a difficult time."

In October, Mr Khan warned rough sleeping will “get worse before it gets better” after damning figures highlighted a record number of people on the streets in the year to March 2023.

In the ten years since 2014, it has spiralled by 58 per cent. London boroughs spent £4 million a day on temporary accommodation for homeless people in the 2023-24 financial year.